How I SBT - V

So far, we have everything we need to write the build definition for a single project. Today, we’ll see another powerful feature of SBT: Multi-module builds.

- How I SBT -

build.sbt - How I SBT - Settings & Tasks

- How I SBT - Plugins

- How I SBT - Build Code Organization

- How I SBT - Multi-module Builds

- How I SBT - Publishing a Plugin

- How I SBT - Final Edition - a la carte

Multi-module Builds

A multi-module1 build is when you have multiple projects, contrasting with the single project we saw in earlier posts. It is particularly useful for building libraries- cats or Http4s, for example.

Http4s is an open-source “suite” of libraries. The Http4s repository is not a single library but a suite of libraries built and published together. Generally, in a multi-module setup, all the libraries in the suite use a single2 version. Http4s has sub-projects such as core, client, ember-core, etc., the build definition of which you can find in the root build.sbt.

Say you want to set up a multi-module build for hamster, an imaginary open-source project. Imagine hamster has the following libraries or sub-projects: core, utils, and client. Following is the folder structure:

hamster

├── build.sbt

├── core/

├── utils/

├── client/

├── project/

├── plugins.sbt

├── build.properties

Here is what would go in the build.sbt:

ThisBuild / version := "1.2.3"

ThisBuild / organization := "hamster"

ThisBuild / scalaVersion := "2.13.15"

ThisBuild / resolvers ++= ....

ThisBuild / credentials := Credentials(...)

lazy val hamster =

project

.in(file("."))

.settings(publish / skip := true)

.aggregate(core, client, util)

lazy val client =

project

.in(file("client"))

.settings(

name := "client",

libraryDependencies ++= ...,

...

).dependsOn(core)

lazy val `core` =

project

.settings(

libraryDependencies ++= ...,

...

)

lazy val `util` =

project

.settings(

libraryDependencies ++= ...,

...

)

Breakdown

Let us break it down:

- If you remember part 1, I mentioned I prefer not to litter settings globally but use the fluent API to declare my build definition. I also mentioned that there is an exception to the rule -

ThisBuildThink ofThisBuildas the parent scope for all the sub-projects in this build. In other words, the settings inThisBuildshall be applied once for all the sub-projects in the build. For example,version,organization, andscalaVersionare applied once for the entire build (for all the sub-projects). - Generally, the root project of the sub-projects is named

root. But I prefer naming it by the project’s name,hamsterhere, so it is easy to distinguish multiple open project windows in your IDE. It is annoying to seerootin every project window. - The root project

hamsteris also a sub-project of the build. The sole purpose of the root project is to be an umbrella for the actual sub-projects -core,clientandutil. - There is no reason to publish3 the root project to the Artifactory. Hence,

publish/skip:= true. - Note the

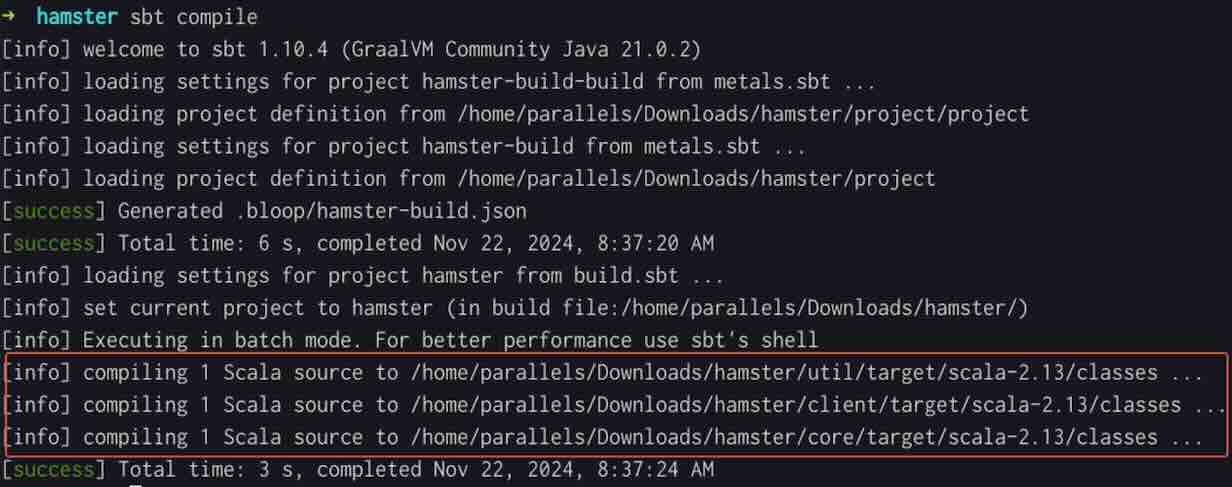

aggregate, which is the primary reason for declaring the root project. It tells SBT to run the commands issued on the root to cascade to all the sub-projects. So, if you issuecompileto the root project, the sub-projects will also be compiled.

- When you

sbt publishLocal(orsbt publishon CI) on the root, the command is cascaded to the sub-projects, which then upon successful compilation, gets published to the local repository (or Artifactory). It is a huge convenience, primarily when published with a single version. - If you don’t declare a root project, sbt will automatically create a default one that aggregates all the sub-projects.

- You can control aggregation by switching off for a particular task. Say you do not wish to publish altogether but issue individual publish commands to the sub-projects (no good reason), then you might set

publish / aggregate := false:

lazy val hamster =

project

.in(file("."))

.aggregate(core, client, util)

.settings(

publish / aggregate := false,

publish / skip := true

)

- The sub-projects -

core,clientandutil, are declared inbuild.sbtsimilar to how we declared one for a single project in previous posts.- Note

lazy val client = project.settings(...).... It is shorthand for:

lazy val client = project .in(file("client")) .settings(name := "client") - Note

- You can issue SBT commands to a single sub-project besides the root, like so:

sbt 'project core' compile test - With such a build configuration setup, you can centralize and share settings that are common to all sub-projects. Lots of such nice things in SBT. Same level of care and discipline in build code as in application code.

- Inter-project Dependencies: Note that

clientprojectdependsOn(core).corecould depend on some other sub-project (none inhamster). By saying so, we let SBT know how our sub-projects are related. SBT uses the information to build the dependency/build graph. In other words, SBT now knows it can compileutilandcorebefore (and maybe in parallel), but can compileclientonly after compilingcoresuccessfully. - So far, we see only one

build.sbt, the root. Sub-projects can have individualbuild.sbt, in which case thebuild.sbtis included in the build automatically. However, in that case, it is not possible to establish dependencies. You can test that out by compiling at the root, and you will see thatclientmay get built beforecore. - When there is a separate build.sbt in a sub-project, the definition in the root

build.sbt-lazy val core = project., references the project definition incore/build.sbt. You will use one of two models:- All project definition listed in

/build.sbt <root/build.sbt>is a simple orchestrator, while individual project definitions are under the sub-project folders.

- All project definition listed in

Try going for #1 as much as possible because of its flexibility, particularly in establishing inter-project dependencies.

Cliffhanger

Multi-module builds are a powerful feature in SBT. Most open-source libraries set up their repository for multi-module builds. In my experience, SBT provides the best and most seamless support for multi-module compared to other build tools. Is it ironic to say, “You will see the truth in my bias if you use it and see for yourself”? 😀

I plan to wrap up the series next time. I will discuss some tidbits and a few final good words about SBT.