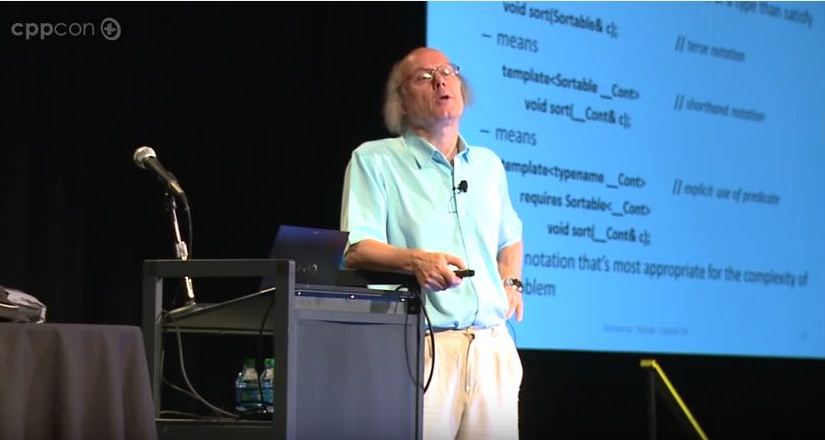

In his talk at the CppCon 2014, Bjarne Stroustrup explained, politely and brilliantly, how to write succint expressive yet intent-ful code. The task is especially hard when there are parties interested in trolling rather than contributing. Like Stroustrup explains back, it is difficult to find the real meaning out of a large block of (legacy) code.

It doesn’t matter if you are modifying the code or just educating yourself. But having blocks of code that do not account for their size, clarity, or lack thereof, and intent is just unwanted fat in the system. With business applications, especially pillared and sustained with legacy code, it has become a defining characteristic of large sized applications – large bulky and ugly code. Just like Jon Bentley once said.

Most programmers have seen them, and most good programmers realize they’ve written at least one. They are huge, messy, ugly programs that should have been short, clean, beautiful programs.

Even with application frameworks and libraries doing most of the work nowadays, we invent new ways to build and maintain the application size. Sometimes, I wonder if the application size is a matter of pride.

Donald Knuth summarized application development: All application writing is sorting and searching. Likewise, it is typical of any application, irrespective of its size, to process data, say primarily as collections – array, list, map or anything that you can iterate over, in various ways. The term process here denotes how a collection is treated in a specific context with various mechanisms to generate a result, be it a collection or not.

For instance, in a particular scenario or context, the application might want to treat a collection of users in the following way:

Iterate the list of users,

find those that live in a specific city (say San Francisco)

and who own at least two cars

group them by their zip codes.

The above problem statement is clear in its intent and the expectations of the result. In other words, the process here is to iterate, find and group the result by some key K; carry data through a pipeline to obtain the desired result. When this is implemented, most programmers model it around data rather than the pipeline, which makes it hard to understand and maintain the relevant piece of code. If we could decouple the context (or mechanics), it becomes easy to convey the intent. I am trying to apply this process over this data subject to these conditions.

Wouldn’t it be a boon to be able to code likewise? Absolutely! However, on the other hand, it is not uncommon to hand-code such data processing using conventional loops that bundles everything from the skeleton that establishes the data pipeline to the mechanics involved in generating and passing intermediate data until the final result is extracted out of the pipeline. Even after carefully hand-coding, it is very likely for this block of code to be duplicated partly or wholly either because the context enforces a different evaluation for the same collection or it is altogether a different collection. In any case, the final and relevant code would then be of an intimidating size to spin folklores – beware of modifications. So in the case when the code really bears a defect or requires an update for a feature, we are forced to triplicate the block(s) of code. Thus are large applications developed! 😀

Data processing or handling is a fundamental task performed in any application. Only if there was an elegant way to express it in a language. Think LINQ!

LINQ (Language INtegrated Query) is an innovative language construct introduced in C# and VB during the .NET 3.5 release. LINQ establishes a uniform surface area for working with collections – objects, SQL data rows, XML elements etc. In other words, LINQ makes querying a first class citizen in C# and VB.

Here is a C# LINQ snippet that queries a given list of File objects for .txt files ordered by their modification timestamp descending.

var query = from file in fileList

where file.Extension.Equals(".txt")

orderby file.LastAccessTime desc

select file;

While the construct of querying remains the same for any collection – objects, XML elements, SQL data objects etc., the context dictates what data is channeled through the pipeline. For instance, there might be a scenario where the resultant collection needs to be ordered by name probably ascending. Or maybe we would want to filter by a different extension. Despite all such contextual differences, the way we express in LINQ makes the code short, clear and expressive!

In the above snippet, note that the variable holding the resultant collection has been named query. You can call it anything but the name is indicative of an important and fundamental aspect of LINQ – lazy evaluation. The resultant collection is realized only when queried. In other words, the elements of the resultant collection are streamed out of the pipeline on demand. For instance, only when the query is used in an iteration to loop over the result …

foreach (var file in query)

{

Console.WriteLine(file);

}

or explicitly queried for the resultant list.

var files = query.ToList();

Until the point of evaluation, query is just an object that you can pass around without worrying about its weight. So it is very much unlike conventional loop oriented code.

Similar to SQL, LINQ has all querying clauses from filtering (where) to joins and group by. It is important to understand that such querying is available in C# as a language construct, not a library of classes and types, and is equally efficient as a hand-written iteration. There is a lot more to LINQ than meets the eye.

If only you are programming in C# … Java continues to live with for loops and if-else blocks. Say hello to JINQ!

JINQ (Java INtegrated Query) is an ultra minimalistic library inspired from and mimicking the .NET LINQ. While LINQ is a language level construct, JINQ is composed of types – classes and methods, but to the same effect.

If the above File example was written using JINQ, it would be as follows:

static final Predicate<File> isTxtFile = new Predicate<File>() {

@Override

public boolean evaluate(File file) {

return f -> f.getName().endsWith(".txt");

}

};

static final Comparator<File> lengthComparator = new Comparator<File>() {

@Override

public int compare(File left, File right) {

return left.length().compareTo(right.length());

}

};

static final Func<File, String> nameFunc = new Func<File, String>() {

@Override

public Name apply(File file) {

return file.getName();

}

};

final Iterable<String> query =

new Enumerable<>(fileList)

.where(isTxtFile)

.orderBy(lengthComparator)

.select(nameFunc);

for (String fileName : query) {

System.out.println(fileName);

}

Alright, I know what you are thinking. How in the world is this code written using JINQ short, succinct or expressive? I purposely made it look big, fat and ugly. Let’s unravel.

First, let us look at the query definition:

final Iterable<String> query = new Enumerable<>(fileList)

.where(isTxtFile)

.orderBy(lengthComparator)

.select(nameFunc);

This is equivalent to what you would write in LINQ. Similar to LINQ, JINQ enforces the construct (although through static types). For instance, even though JINQ is driven by types and methods, the construct ensures you cannot call methods (clauses) at random. The query begins with creating an Enumerable indicative of the from clause in LINQ and typically ends with a select clause after which you would query the results over iteration or instantly (using toList() or toDistinct()).

Typical data processing scenarios in an application consume functions such as filters, transformers etc., that power the data pipeline. Such functions are often used repeatedly, and are inherently reusable. Hence, the above code declares such data functions static hinting that they are declared outside of the query context to reduce clutter in the query code, and is indicative of a lambda. You have to swallow that verbosity if you are using Java versions older than 8.

In Java 8, these discrete declarations won’t be necessary to reduce clutter in the query code because lambdas come to the rescue.

// JINQ with Java 8

final Iterable query =

new Enumerable<>(fileList)

.where(f -> f.getName().endsWith(".txt"))

.orderBy((left, right) -> Long.compare(left.length(), right.length()))

.select(File::getName());

The select method can be used to return a collection of the primary type (File in our case) using the no-arg overload (select()) or transform the primary type to some desired resultant type (String in our case) using the select(Func selector) overload.

Like LINQ, the fun part with JINQ is that the query is evaluated to generate result on-demand; iteration or instant realization. However, queries that use orderBy and/or groupBy, are evaluated slightly different. Since an orderBy or groupBy alters the source collection of the pipeline, the intermediate result is fully evaluated until that point (although lazily), and the result from the rest of the pipeline will be generated on-demand (assuming there are no other orderBys or groupBys down the line).

Will JINQ be able to perform everything that LINQ does?

Absolutely not! Because certain things are almost not possible at the type level such as intermediate variable declaration using let keyword or anonymous type declaration in a select clause or the use of var to capture the resultant type. Because the language (Java) does not have facilities to support such things.

What is possible though but not yet supported in JINQ is the seamless integration of other collection-based or collection-like entities such as XML elements, SQL data objects etc. While a naive provision (IClauseProvider) is available, the full extent and implementation of such an extension were not beyond what was needed for me at the time. Perhaps, it is food for thought for a later day!

JINQ is not complete per se to be at par with LINQ. But it is definitely functional. Sammy and I are working on adding join, chaining mutiple source collections ( chaining froms to achieve SelectMany) and a few more things. Even without the above forthcoming features, JINQ is equally powerful and can enormously reduce the code bloat making your code expressive with respect to querying objects. Try it with some of your big fat classes and methods and see for yourself.

Head over to github, download, use and share your comments on JINQ.